This page contains the GCSE AQA Mathematics Surds Questions and their answers for revision and understanding Surds.

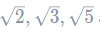

Square numbers are the result of multiplying a number by itself, e.g.3×3=9. The opposite of squaring is to take a square root, e.g. of 9is 3. This works fine for square numbers like 1, 4, 9, 16, etc, but what about other numbers? Well, if you put square root of 3 into your calculator you’ll see that you a get a nasty decimal as a result: 1.7320508…

As it happens, this decimal goes on forever and has no pattern – it’s what we call an irrational number. So, no matter how many digits of it we write out, we’re always going to be missing some. As a result, we often choose to leave the number in the form:square root of 3. This is a surd, and has the benefit of being exact, unlike any rounded number that the calculator might give us.

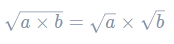

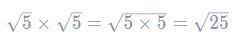

More generally, we get a surd when we take the square root of a number that isn’t a square all surds. Like many things in maths, surds can be simplified. The process of simplifying surds is based on this multiplication rule:

If you’re not convinced by this, try testing it out with a few different numbers to see it in action. Let’s look at an example of how we can use this to simplify surds.

Example: Write simplified surd form.

![]()

To do this, we need to think of a square number (bigger than 1) that goes into 28. 4 goes into 28, so we will use that. Specifically, 4×7=28, so using the rule above, we get

Now, the reason we were looking for a square number that went into 28 is because at this point, part of our number is square root of 4, which we know to be 2. So, replacing square root of 4 with 2, we get

This is now in what we call surd form, which means it can’t be simplified any further. To check if it can be simplified further, see if there are any square numbers that go into 7 (since 7 is now the number inside the square root). Clearly, there aren’t, so we’re done.

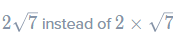

Note: with surds, like with algebra, we often miss out the multiplication symbol and write

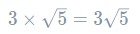

If a question asks you to leave your answer in surd form, you should always simplify it. If it’s a question in a calculator paper, your calculator will handle surds for you. Now, the next part of this topic is on rationalising the denominator. Earlier, we mentioned that surds are irrational numbers, and we don’t like to have irrational numbers on the bottom of a fraction. So, by cleverly applying that multiplication rule mentioned above, we can make the denominator rational.

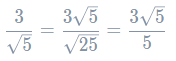

Example: Rationalise the denominator of

![]()

As we know, you can multiply the top and bottom of a fraction by the same number without changing the fraction. In this case, we must multiply top and bottom by whatever surd is on the bottom of the fraction, here that’s square root of 5. So, the numerator becomes

Now, applying the multiplication rule from above in the other direction, the denominator becomes

But we know the square root of 25 – it’s 5. So, the fraction becomes

The denominator no longer involves a surd, only a 5 – which is a rational number – and so we have successfully rationalised the denominator. As mentioned, the aim is to always multiply top and bottom by whatever surd is on the bottom, because that way we will always end up with a square number inside the root on the bottom, which we can then happily take the square root of.

There is another form of irrational denominator that you have to know to rationalise. This one is trickier, but it applies the same principles we’ve seen so far.

Example: Rationalise the denominator of the following fraction.

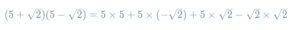

Okay, so the way to do this will seem random initially but we’ll see why it works. To rationalise the denominator of this fraction, we are going to multiply top and bottom by (5-sqrt{2})(5−2). This is going to involve some bracket expanding – this should be treated in exactly the same way that bracket expansion is when you do algebra. The numerator becomes

![]()

Now, sorting out the denominator will involve double bracket expansion. If it helps you to use FOIL and/or draw lines between terms you’ve multiplied, then do that. The denominator becomes

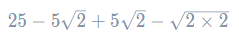

Take your time to make sense of what’s going on; it is complicated. So, we have the denominator

Now, this is the point where it finally starts working. Remember: the aim is to end up with no surds on the bottom. The first term is 25, so that’s not a problem. Now, the middle two terms are square root of−2 and 5sqrt2. Since the first one is just the negative of the second one, these two terms cancel each other out – we’re left with zero lots of sqrt

2. Then, finally, the last term is ![]() which is another rational number and so is not a problem. So, given that the middle two terms cancel, the denominator becomes

which is another rational number and so is not a problem. So, given that the middle two terms cancel, the denominator becomes

25+0−2=23

Therefore, the fraction is

There are no surds on the bottom, so we have succeeded. So, the key to picking what to multiply top and bottom by here is: take whatever is on the bottom, change the middle sign (either from + to – or from – to +, and then you’ve got your answer. Just take your time with all the working out.